The Thinker V

thinking in the age of the strongman

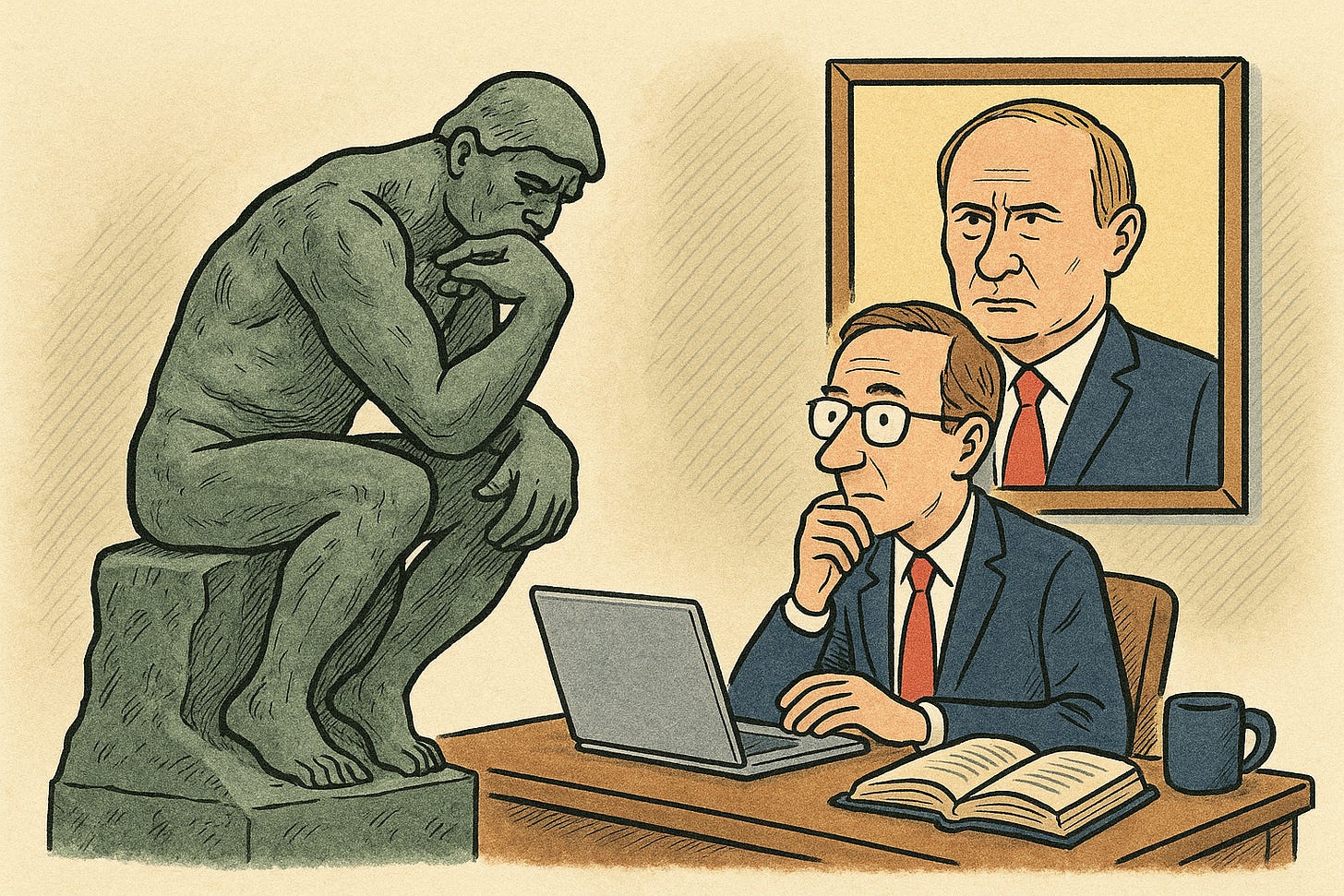

The New York Times reporter was insistent; in the way they usually are. “What does Putin really want?” he demanded.

The Thinker hesitated. He had met Putin a grand total of once for two minutes at a conference. His august personage had been surrounded by security and thronged with sycophants. They hadn’t shared a drink, a cab ride, or even a casual insult. So how could he possibly know what Putin really wants?

But of course, he was supposed to know. The Thinker is an “expert” on Russia—he had once written a book on Putin’s rise through the Russian bureaucracy, tracing his path from KGB to Kremlin. The book, inspired by a now-unfashionable Jungian framework, argued that Putin’s trauma over the Soviet collapse had left him with a kind of post-imperial PTSD, compelling him to invade his neighbors in a desperate search for psychic restoration.

Over the many years he had studied Putin, the man had become increasingly familiar. The Thinker sometimes believed he knew Putin better than he knew Mrs. Thinker. After all, he merely shared an apartment with his wife; with Putin, he shared a brain.

So, he answered as he always did -- as if he had been sleeping under Putin’s bed taking notes as he muttered in his sleep. He had no real idea about Putin’s deepest desires, but neither did anyone else the New York Times talked to. And, more importantly, the illusion of psychological insight passed for expertise.

The Psychoanalytical Turn

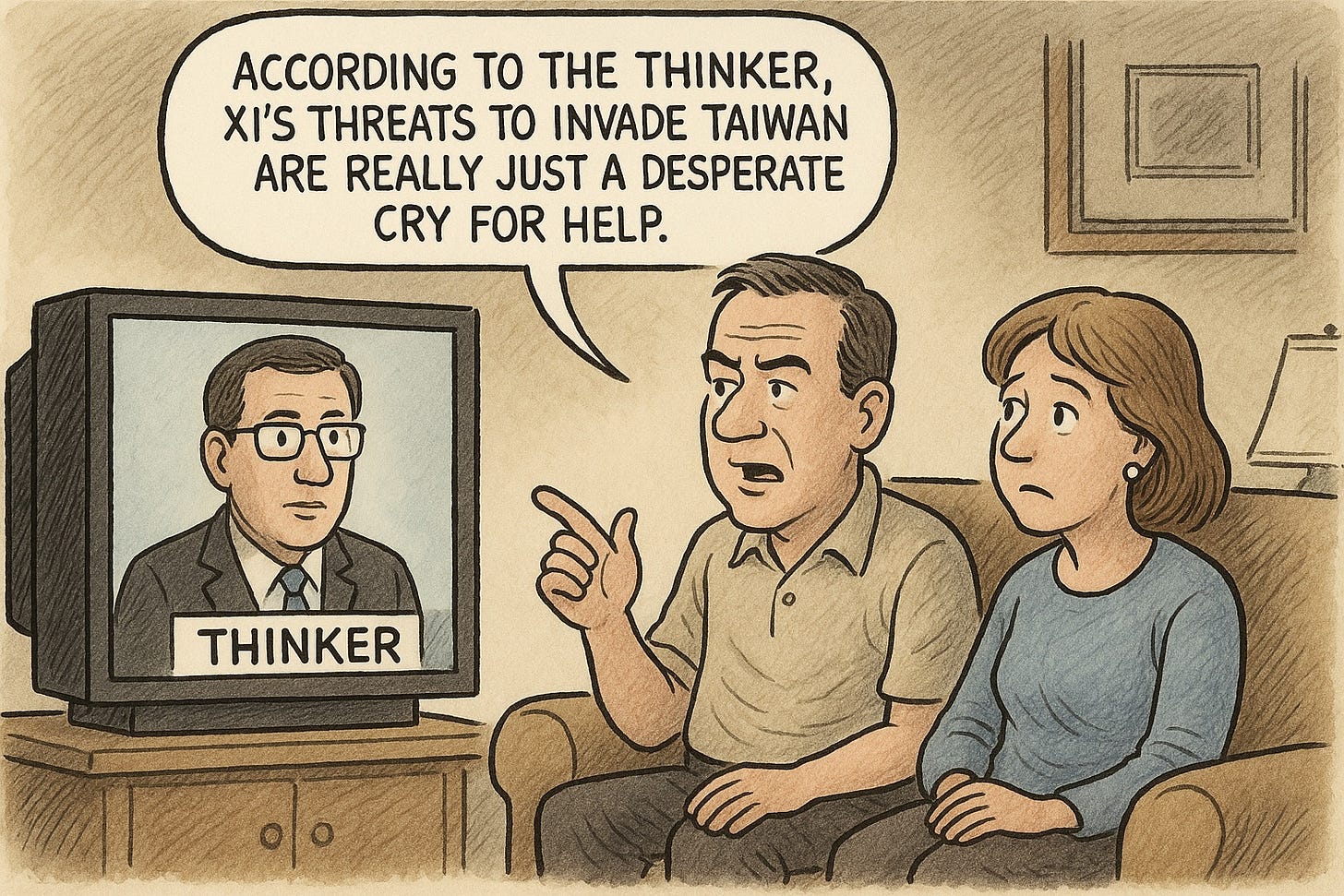

The Thinker wasn’t alone in this approach. That morning, like most mornings, he had sifted through policy briefs, op-eds, and think tank memos attempting to decode the psyches of the world’s most opaque leaders: Trump’s unresolved grievances, Xi Jinping’s filial piety, Erdoğan’s Napoleon complex, Netanyahu’s messianic anxieties. Each dossier read less like strategy and more like a psychiatric file with delusions of statecraft.

This trend didn’t emerge from nowhere. The recent rise of strongmen all over the world encouraged such analysis. The more opaque the regime, the more it became about the man himself. Power was no longer institutional but personalized, and in that personalization came mystique. When a system produces no policy process, only outcomes, one can most easily explain outcomes with personality.

The more opaque the regime, the more it became about the man himself.

Back in graduate school, the Thinker had learned to analyze world politics structurally. They would confidently present a map, circle a few straits or chokepoints, and explain international conflict with a mix of military necessity and economic interest.

But in his current job, analysis required knowledge less of troop movements and supply chains, than of the leader’s parental relationships, body language, and zodiac sign. Missile tests and territorial grabs were read through the lens of ego maintenance or childhood trauma. One memo even suggested North Korea’s nuclear posture could be softened with better father figures and a hug

To be fair, political psychology is a legitimate field. Leader beliefs, cognitive biases, and personality traits can shape outcomes, especially in autocracies where power is personalized and insulated. There is real research, backed by method and data. But the line between scholarship and speculation is thin, and in the rush to explain unpredictable actors, too many analysts slid into pop psychology and amateur diagnosis.

The Temptation of the Man

The danger of this tendency, the Thinker admitted in his quiet moments, was not just intellectual laziness. It was analytical distortion. By reducing geopolitics to personality, we turned complex systems into cartoonish dramas. International relations became a Netflix series: predictable arcs, overacted villainy, and a surprising number of returning characters.

These narratives offered a certain comfort. If conflict stemmed from one man’s neurosis, then history could be undone with therapy—or regime change. But this perspective obscured deeper forces: national interests, bureaucratic incentives, elite competition, demographic trends. Even the most authoritarian leader operates within constraints: political, institutional, and informational. To pretend otherwise was to turn strategy into mythology.

The personalization of foreign policy also had moral consequences. It allowed us to frame adversaries not as geopolitical competitors but as villains in a morality play. That made it easier to dismiss their motivations as irrational or evil and harder to reckon with the structural tensions between states. In doing so, we externalized the problem and avoided introspection about our own role in a fraying global order.

And so, every crisis became a case study in psychoanalysis. Every analyst a kind of geopolitical Freud, interpreting military exercises as dreams and trade policy as repression. No one admitted how little they really knew about the men under whose beds they metaphorically hid—least of all the Thinker himself.

The Tyrant’s Tummy

The interview done, the Thinker leaned back in his chair and stared out his window at the familiar view of rooftop HVAC units and faded flags of obscure embassies. He wondered idly what Putin had eaten for lunch—borscht, or maybe something heavier? Some claimed foreign policy was shaped by ideology or grand strategy; the Thinker suspected fiber content played a larger role.

He opened a blank document and began typing a new column, tentatively titled The Tyrant’s Tummy: How Putin’s IBS Explains the Ukraine War. He wasn’t sure it made sense. But the act of writing it gave him a fleeting feeling of clarity. In a world of strong men and weak institutions, that was sometimes the best a Thinker could do.